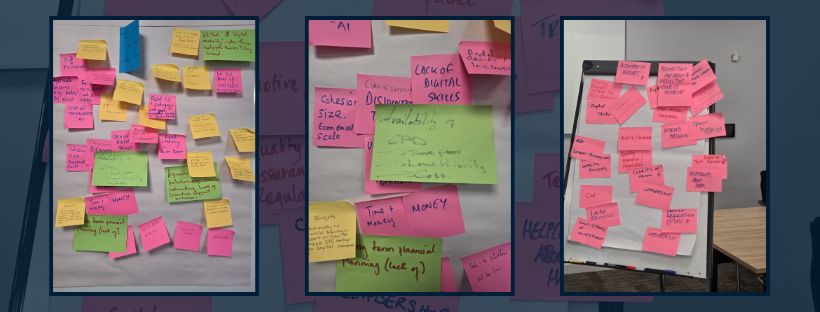

Barriers and challenges

The workshop began by mapping the many barriers to digital maturity raised by participants. Although the issues were wide-ranging, they consistently clustered around five overarching themes. These themes capture the human, technical, financial, structural, and systemic obstacles that schools face, and show how these barriers are deeply interconnected. They also provided a foundation for understanding both the evidence gaps and the solution areas that followed.

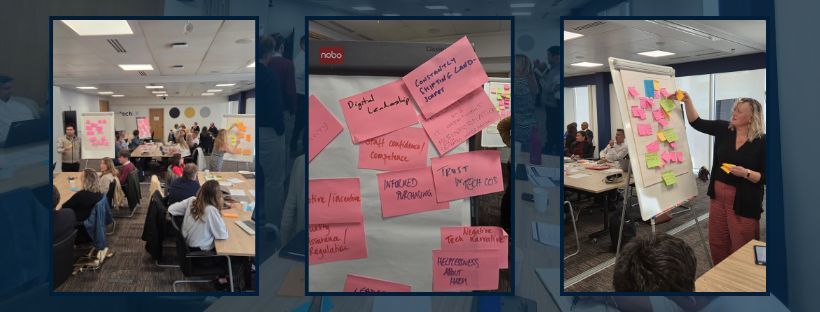

People: Confidence, Skills and Leadership Gaps

The confidence and capability of all staff including leadership was consistently raised as an enduring challenge to digital maturity and effective use of Edtech. The national Edtech Hubs & communities of practice, led by LGfL and Edtech UK, continue to demonstrate the importance of peer mentoring and professional development. Lack of time was a central issue: teachers and school business professionals are rarely given space or structure to upskill in tech, and leaders struggle to dedicate time to building the knowledge needed to make sound choices about technology. This reinforces wider confidence gaps, leaving both groups uncertain about what to adopt and why.

Participants also pointed to a perceived risk-averse appetite and constrained entrepreneurial thinking in school cultures, which in turn limits innovation. It was felt that Ofsed did not encourage new ways of thinking; or themselves had limited knowledge of the benefits of digital to support organisational excellence, to support teachers or to support learning. This may have been, in part, due to past “false dawns”, wherein technology innovations promised more than they delivered, leaving staff, communities and policy makers sceptical of the impact of future technology trends. Similarly, inconsistent professional development has allowed these doubts to solidify. Past failed initiatives could also be due to what was identified as siloed implementation of technology change, with Edtech appearing imposed rather than co-owned. Finally, staff contributions were seldom recognised, reinforcing the view of Edtech as ‘peripheral’.

Foundations: Uneven and Legacy Infrastructure

Participants repeatedly pointed out that schools are starting from very different foundation blocks. While some have reliable networks and support, many still face “infrastructure limitations, especially internal networking” and “lack of specialist in-house support.” Connectivity and device access remain uneven, and without a clear infrastructure package schools are often tempted to chase the “fun side” or shallow use of technology before securing the basics. This often results in Edtech tools running on shaky ground, with predictable frustration when systems fail to deliver.

Infrastructure is also still seen as a sideshow rather than part of core operations alongside finance or estates, which means investment and renewal are inconsistent. Training to manage and sustain infrastructure is perceived as undervalued or missing, and participants flagged cybersecurity and safeguarding as areas where accountability is weak, leaving schools exposed.

Funding and Procurement: Short-Termism and Poor Value

Funding and procurement issues cut across many of the challenges raised. The challenge of unpredictable and what was perceived as insufficient funding streams, make long-term planning difficult for schools. Many wait for government direction before acting, leading to piecemeal adoption and missed opportunities for scale.

Procurement processes were also flagged as being inconsistent, with schools straining to navigate complex technology markets resulting in poor decisions or missed value. Similarly suppliers treat schools unevenly, and return on investment is hard to demonstrate. As with leaders and teachers, past experiences with ill-judged purchases or short-lived products may be fostering cynicism, with cost used both as a genuine barrier and an alibi for delayed investment. What is missing is strategic financial planning tied to technology, better procurement support, and stronger supplier relationships to align investment with real needs.

Incentives and Accountability: No Carrots, No Sticks

The Incentives/Accountability category captured two ends of a series of challenges related to motivation. Accountability frameworks were claimed to have not kept pace with the spread of Edtech. Again, Ofsted inspections and system-level performance measures make little reference to digital, meaning schools face no consequences for poor practice.

Equally, there are few incentives to reward innovation or strong adoption of Edtech. Assessment models remain top-down and unchanged, leaving little room to embed technology in pedagogy or explore digital modes of evidence and progression. The result is a feedback loop where digital maturity stagnates because there is neither pressure nor recognition. Participants noted that while the Department for Education has published useful standards, schools vary in how far these are adopted and embedded.

Vision: The Missing North Star

Finally, several paticipants invited us to step back and ask the most fundamental questions. Participants observed that without a shared national vision, schools and suppliers are left working towards different and sometimes fragmented goals. It was suggested that in the absence of a inspiring narrative of education that unites the role of education itself with the purposeful adoption of Edtech, progress across people, infrastructure, funding, and accountability will remain piecemeal.