Standard of appeal under the SMS regime: a response to the Lords Committee advice

Guest blog by Verity Egerton-Doyle and Nayantara Ravichandran of Linklaters

On Friday 21 July, the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee (“Lords Committee”) issued its advice to the Secretary of State for Business and Trade, recommending that the judicial review (“JR”) standard that applies to the forthcoming Strategic Market Status (“SMS”) regime in the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (“DMCC”) should be maintained. The advice expressed concern that enhancing the appeal standard would fundamentally undermine the viability of the SMS regime. The key reasons given, drawing on the evidence heard by the Committee, were: (i) speed and regulatory capacity; (ii) that JR has been proven to be robust and valuable in comparable regulatory regimes; and (iii) that a JR standard would incentivise firms to be forthcoming from the outset and support a participative regulatory process. The evidence heard by the Committee supporting a change to the appeal standard was dismissed in relatively short order, characterised as having come from (the reader is implicitly invited to infer, self-interested) “big tech firms”.1

In this article, we respond to some of these points. We have already addressed the speed and regulatory capacity point: in our previous article we analysed the timelines of previous comparable appeals and found that historically, JR has not been faster as an end-to-end process than merits review. We argued that – especially given decisions of the DMU are not suspended pending appeal – the evidence does not support the widely-made claim that JR will lead to faster outcomes compared with an appeal process in which the court can determine whether the regulator’s decision is “wrong” (as opposed to having been made through a flawed process), and if so replace the regulators’ decision with its own (where it is holding the evidence to do so). This is a point the CAT itself has made before, writing that “there is no proper basis for the asserting that appeals on a “judicial review” standard will be quicker and shorter than appeals on an “on the merits” standard”.2 We have also previously explained that while JR is a flexible standard, absent clear legislative intent or relevant underlying legislation / convention, the CAT will be obliged to apply “traditional” JR under the DMCC.

Here, we address three other points arising out of the Lords Committee advice: (i) the idea that JR is an “appropriate standard” for decisions of a specialist regulator, that has been successful in comparable regimes; (ii) the suggestion that JR supports a “collaborative and participative” regime while a higher appeal standard would undermine this; and (iii) that more judicial scrutiny would be to the sole benefit of SMS firms. We argue none of these arguments survive closer scrutiny.

Counting the “pairs of eyes”: all other regimes get more than one

It is true that many other decisions of specialist regulators – including decisions taken by the CMA under the Enterprise Act 2002 (“EA02”) – are on their face appealable on a JR standard. However, closer inspection reveals that the SMS regime will be the only comparable regime in which there is a single decision maker (for most decisions, a delegated committee of the CMA Board) and only a traditional JR standard on appeal. Other regimes build in one or both of (i) a multi-stage decision making process; or (ii) a higher standard of judicial scrutiny.

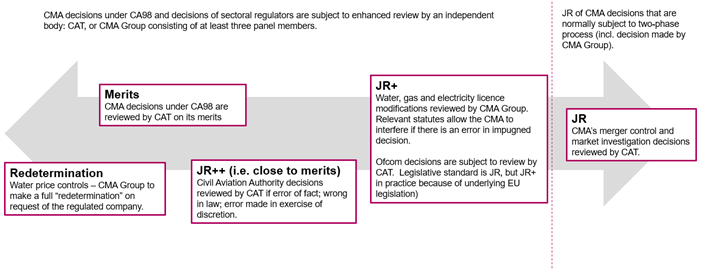

Appeals of decisions by the UK’s sectoral regulators are subject to various bespoke regimes, which we have summarised in the figure below. While the specifics vary, decisions are subject to an enhanced standard of review that can range from JR+ (i.e., determining whether the impugned decision is “wrong”3) to a full de novo redetermination. In each case, the review is conducted by an independent body – either the CAT or a CMA Group comprising of at least three Panel members that are required to act independently of the CMA Board.

The traditional JR standard does apply to CMA decisions made under the merger control and market investigation regimes under the EA02. However, the administrative process under these regimes is far more comprehensive than that contemplated by the DMCC and critically, involves a “fresh pair of eyes”. The CMA’s merger control and market investigation references are subject to a two-stage process.4 In the case of merger control, the Phase 1 decision is taken by the CMA staff while the Phase 2 decision is taken by a CMA Group consisting of independent Panel members. Similarly, a market investigation reference is typically conducted after a market study. There is no similar two-stage process contemplated for decisions made under the DMCC.

In summary, for all comparable regimes, businesses can expect that at least two “pairs of eyes” consider the “merits” of each decision. There is no such check or balance contemplated by the SMS regime, making it a unique outlier among analogous regulatory regimes, and – we argue – leading to the CMA being given extensive discretionary powers without provision for sufficient scrutiny of decision making (whether through an administrative or judicial process).

The impact of the standard of appeal on a “collaborative and participative” regime

The Lords Committee advice suggests that the JR standard will incentivise firms to “be forthcoming from the outset” while a merits appeal would “create incentives for firms to be adversarial” and thus extend the administrative process. The Lords Committee cites the CMA’s evidence, in which it argued JR provides for an effective route for legal challenge without incentivising parties to take an excessively adversarial approach.

The CMA as a responsible regulator will of course want to take lawful and fully reasoned decisions no matter what appeal standard they need to meet. However, the CMA’s arguments on this point (explained further in its own submission to the Public Bill Committee) rely on a comparison with CA98 enforcement for which the CMA says full merits appeals “turn regulatory relationships into adversarial contests”. We would respectfully disagree that CA98 is a good analogue for the SMS regime: proceedings under CA98 are inherently and unavoidably adversarial because the purpose of the process is to find and fine infringements of competition law.

By contrast, under the SMS regime, the CMA will be taking a much broader range of decisions and the act of SMS designation establishes an ongoing regulatory relationship with the CMA’s Digital Markets Unit (“DMU”). The participatory nature of the SMS regime under which the CMA will be responsible for administering Codes of Conduct with a set of clear ex ante rules is entirely different to a one-off proceeding relating to particular (most often, historical) conduct. There is a clear difference between proving harm from activity already undertaken (CA98) versus demonstrating the violation of what will be pre-established, collaboratively developed, and prescriptive rules (DMCC).

In any event, given that orders and directions of the CMA under the SMS regime are not suspended pending appeal (unless the CAT orders otherwise), SMS firms have no incentive to bring a “vexatious” appeal purely for the sake of delaying or slowing down the operation of the regime, because it would not do so. The committee heard this in oral evidence from Meta.5 If one were to assume nefarious intent on the part of one or more potential SMS firms, the incentives to bring an appeal that will not change the final outcome are higher on the JR standard than they would be in a merits appeal. This is because a successful JR – even on a purely (albeit meritorious) procedural point – would lead to the decision quashed and therefore inapplicable during a remittal process. By contrast under a standard of appeal in which the CAT can replace the CMA’s decision with its own, the CAT could in many cases correct the error (or as the President of the CAT has put it, “rescue” the finding).6 In this context, it is worth highlighting that in appeals of CMA merger decisions (on JR standard), the conclusion on whether or not a merger raises competition concerns has never changed on a remittal.

There is no reason to believe more rigorous scrutiny of decision making would be to the sole benefit of SMS firms

Much of the discussion around the standard of appeal has been focussed on the rights of the potential SMS firms. These are of course important and should not be lightly dismissed: the scale of the powers wielded by the CMA under the SMS regime is immense, could force fundamental changes to business models and have financial implications in the billions of pounds. But SMS firms are not the only parties who may find themselves aggrieved by decisions under the SMS regime. Applications for review can be made by any party with a sufficient interest in the relevant decision. Competitors and customers will likely be directly affected by many conduct requirements. Granting the CMA (near) unlimited discretion does not safeguard their interests any more than it does those of the SMS firms.

The DMCC delegates enormous power to the CMA. The markets and modalities in which SMS firms provide their services are highly complex and fast evolving. They are difficult to understand, and there is inherent and unavoidable uncertainty about how technologies will develop. The DMU is being handed an enormous and difficult task, and while it is being staffed with experts and specialist teams to enable it to take well evidenced and robust decisions, it will inevitably make mistakes. This issue is particularly acute because the DMU is subject to more constrained timetables than many other CMA decisions. For example, the designation and code of conduct process is intended to run in parallel and be concluded within just nine months. By contrast, the CMA has 12 months to conduct a market study and an additional 18 months (extendable to 24 months) for a market investigation (i.e. 2-3 years total).

The risk that a complainant is disadvantaged by the JR standard is not purely theoretical. For example, in the private healthcare market investigation, the CMA dismissed concerns over the formation and operation of anaesthetists groups. AXA PPP appealed the CMA final report, arguing there should be an evidential presumption of an adverse effect on competition where groups with a high market share collectively set prices. In rejecting AXA PPP’s appeal, the CAT emphasised that the JR standard meant it had a limited role in a challenge brought under EA02, and that the CMA had wide discretion to make choices as to how it prioritised its workload, especially where deciding to pursue this dimension of the market investigation further could have jeopardised the CMA’s ability to meet its statutory timetable.

It is not difficult to imagine similar scenarios arising under the DMCC. Publishers, for example, have been clear that they hope the DMU will intervene to help ensure they are getting fair commercial return for their content – should the DMU investigate and conclude no action is needed, they have the right to appeal. But unless the appeals standard is strengthened to consider the merits, their appeals will in effect be restricted to process grounds only. Even if successful, such a complainant would then need to wait for the DMU to re-run its investigation before getting any relief, as it will not be open to the CAT to “rescue” the decision even if there is a clear route to do so.

The SMS regime puts the CMA under radically more time pressure to diagnose problems and impose remedies and while these time limits are imposed for good reason, there is a real risk – to misuse a big tech motto – that the DMU will “move fast and break things”. To assume a higher level of judicial scrutiny is to the sole advantage of SMS firms would be to assume that the only errors the DMU will make are those of over-intervention, to the detriment of SMS firms. The history of perceived under-enforcement that has led to the SMS regime would suggest this is not a good assumption.

Conclusion

In this note, we have addressed three of the key points arising out of the Lords Committee advice. As we have explained, the proposed standard of review for the SMS regime is a unique outlier: there are no comparable regulatory regimes (including the oft-cited CMA merger and market powers under the Enterprise Act 2002) that hand a regulator so much power with so few checks and balances – either internal, judicial, or both. In relation to the impact of the appeal standard of how participative and collaborative the regulatory process might be, we have also explained why we believe the CMA’s experience in enforcing CA98 is a poor analogue and that in any event, the fact decisions are not suspended pending appeal changes incentives. Finally, we have explained that while it is true that the majority of the evidence heard in favour of a higher standard of appeal by the Lords Committee came from “big tech”, providing for a higher level of scrutiny of CMA decisions could just as readily be to the advantage of potential complainants as it would be to the advantage of the SMS firms themselves.

1. Evidence given in support of a change to the appeal standard came from various witnesses, not limited to those representing large tech firms. One of the two independent competition law experts who gave evidence (Liza Lovdahl Gormsen) supported a change to the appeal standard to allow a time-limited merits review while the new regime to “embed”. Transcript available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13402/pdf/.

2. Lords Digital Committee Inquiry on the DMCC - Q21.

3. Speech of Sir Marcus Smith at the CMA Judicial Review Conference, 18 April 2023, at para 43: DISCRETION (catribunal.org.uk).

4. We note for completeness that a market study is not a pre-requisite to a market investigation. For example, in 2011 the OFT referred the market for statutory audit services for large companies to the Competition Commission for a market investigation. It did not believe it required a market study to determine that the statutory thresholds were met on the basis that it had kept the market under review for some time and had access to information on whether a market investigation was required (see here). However, in recent years most market investigation references have arisen from prior market studies or references by sectoral regulators.

5. Response of the Competition Appeals Tribunal to the Government’s June 2013 “Streamlining regulatory and competition appeals” consultation, page 22.

6. The Communications Act 2003 regime in particular is often cited as an example of how flexible JR can be, but as we have explained previously, that regime evolved as a result of underlying EU legislation and absent clear legislative intent or other legal basis (e.g. the ECHR), the courts will have no choice but to apply “traditional JR” in appeals under the DMCC.