Speeding Up Solutions to Reduce Reoffending

Recent and Ongoing Policy and Technology Changes are Improving Access to Justice

Numerous policy developments in HM Government departments are improving justice for UK citizens. These include better access to justice and legal aid, streamlining the preparation of court cases using digital exchange of information, new case management for court cases, and trialling of tablets in courts to manage the presentation of evidence to juries. These examples are focused on improving the front part of the justice value chain, before sentencing. However, reducing reoffending is a critically important objective that can improve justice and change lives for tens of thousands of people. Yet many challenges continue to slow down and hamper this desired outcome. While current HMG statistics show an improving trend with 2% to 3% improvements, the total reoffending rate is 24.7% overall, and for those prisoners who have less than 12-month custodial sentence the reoffending rate is 57.5% (see Reoffending statistics GOV.UK).

UK prisoners who reoffend face huge challenges individually and with their families. Reoffending also drives increased needs for prison places, prison officers & other staff, increased material requirements in the overall HMPPS estate, as well as a greater court caseload. Reoffending impacts all parts and aspects of justice. Most importantly though, MOJ research demonstrates that reoffending is often the outcome of a vicious circle of those in prison being unable to acquire relevant new skills and move into stable employment and accommodation when they leave prison.

Current and planned solutions to reduce reoffending bring together people and technology to address new skills through training, preparation to secure accommodation after leaving prison, and identifying suitable work. These approaches have shown success in new-build prisons and those existing prisons where in-cell technology and network connectivity is available. Most prisons in England & Wales do not currently provide the necessary networking and devices for prisoners to access the new technology for training, finding work and accommodation. This is because so many prisons and establishments are extremely difficult environments to rollout the required connectivity.

Prison Connectivity Takes Time

HM Prison and Probation Service has an extensive programme of work called the Prison Technology Transformation Programme (PTTP). This will eventually cover all prisons and establishments in England & Wales to provide secure Wi-Fi for staff use and in-cell devices for prisoners, among many other improvements. Rolling out restricted Wi-Fi is very difficult in a large percentage of prisons due to thick walls and other building fabric which limits coverage from each wireless access point. This means more are needed to cover the whole building. To exacerbate the hurdles, each access point needs electrical power as well as network cabling, and the older prisons weren’t built with such infrastructure needs designed in. It’s therefore understandably difficult and time-consuming to equip many of the nation’s prisons with connectivity, and this is an essential pre-cursor to achieving the benefits from in-cell devices and prisoner applications. The MOJ Prisons Strategy White Paper of December 2021 had a target to have connectivity in a 16 HMPPS establishments out of a total of 122 (see Prisons Strategy White Paper).

Technology Hierarchy of Needs

Like a technology layer cake that’s analagous to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it’s clear that technology solutions which deliver business and policy outcomes are themselves dependent on multiple layers of enabling technology and foundational capabilities. This has been discussed in many papers including the World Economic Forum’s article on Digital Needs Framework in 2019 (Michelle Lau, Dentsu Aegis). The foundational technology of wireless network connectivity in prisons is essential before applications to support staff and prisoners can scale up to be accessible and valuable to all who need them. If achieving a reduction in reoffending is a goal to be desired as quickly as possible, then the key question for this paper is what options exist to speed up the delivery of foundational capabilities like Wi-Fi?

An obvious thought is to double or triple the deployment rates for prison Wi-Fi. The same amount of total effort would be expended, and the identical equipment will be rolled out, so it would be a matter of spending budget over a shorter period to achieve strategic benefits sooner. Operational cost savings and societal benefits from reduced reoffending would more than outweigh the shorter-term increased cost of delivering connectivity. However, there are practical limits on how many staff can work in parallel to survey, analyse, plan, assure, and implement the changes for power cables, network cables, building changes, and network equipment deployments within sensitive and secure environments that don’t have “down time.

A Different Approach with Current and New Technology

Multi-sourcing and supply chain diversification is a well-used technique in product manufacturing, retail, and e-commerce to ensure a product or service that is in high demand and short supply can be delivered to customers without long delays or unfulfilled orders. Essentially, it’s simply using a number of parallel sources to increase availability. There are endless contemporary and historical examples. When British Railways modernised from steam traction in the 1950s and 60s, they used multiple locomotive designs and several different suppliers with varying hardware to speed up their traction replacement programme.

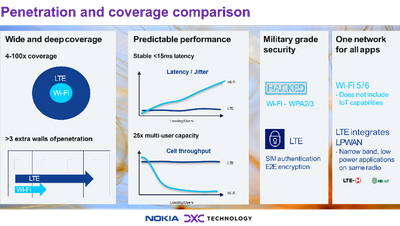

In prisons, rather than relying solely on Wi-Fi as a way to provide connectivity, it’s possible and proven to use more than one wireless networking technology. Private 5G and private LTE are data networking technologies like those used in mobile phones. It’s the same technology but using different radio frequencies. This means secure and private radio networks can be used instead of the public mobile networks that we use for our smartphones. There’s a cost for using private radio spectrum, but this is balanced against a long list of benefits and savings. Private LTE (pLTE) is best suited to the needs of in-cell devices in prisons for two reasons.

The coverage and penetration of pLTE is better than 5G, and the data bandwidth needed for in-cell applications does not require 5G. Using pLTE in difficult prison environments would allow connectivity to be rolled out using only a handful of network access devices and antennas rather than much larger numbers of Wi-Fi devices. The power and network cabling needs would be limited to the small quantity of devices, and these can be mounted in places within prisons that are much easier to access. This means the rollout of these pLTE networks in prisons could be achieved more quickly than Wi-Fi. If this were coupled with continuing the rollout of Wi-Fi, then both technology types could have different implementation teams which could more than double the pace of rolling out connectivity. LTE connectivity is built-in to many modern end-user devices like laptops, phones, and tablets, and it can be easily added to older devices that don’t include LTE.

There are many hardware vendors for pLTE networks and there are also suppliers who offer fully and partially managed services. LTE as a technology has been proven for over a decade and private LTE has been available in the UK for several years now. There are UK companies who are using pLTE to provide data networking, voice communications, safety and sensor connectivity in environments where Wi-Fi is difficult, slow, or costly to deploy. Looking beyond the UK, pLTE is already in use in prisons in several states in the USA, and there are many examples of its use by both public and private sector organisations.

Other Benefits and Other New Technologies

MOJ also has strategic objectives to improve sustainability across the entire estate. Once again within HMPPS, new-build prisons have an advantage in being equipped to support technology that can help to deliver against these sustainability goals, i.e., connected sensors which can enable smarter spaces that can modify lighting, heat, and other controls to reduce energy consumption and emissions. Within the older prisons, such sensors are again dependent on the connectivity before they can help. However, there are UK companies with sensor products that can support this within the difficult environments of older prisons. These sensors can be hardened against heat, dust, water, and physical impacts. The sensors can be pre-fitted with five-year power sources, so they do not need local mains power or power-over-ethernet (PoE), and they are able to connect securely over multiple different wireless technologies including both Wi-Fi, 5G and LTE. The faster rollout of secure network connectivity in prisons in England & Wales can therefore support multiple other use cases for strategic justice objectives.

Conclusions

There are well-defined and accepted benefits for UK justice in speeding up efforts to reduce reoffending. Work is well underway to provide the necessary connectivity in UK prisons. This could be achieved at a faster pace by continuing the existing work in parallel with the use of additional connectivity such as private LTE. The combined results can supercharge the timeline for outcomes achieved from in-cell technology and the applications and support programmes for prisoners to receive training, find a place to live when they leave prison, and find stable work. This parallel delivery of secure network connectivity technology can further be leveraged for additional new technologies such as hardened wireless sensors to improve sustainability in UK justice establishments. However, it would not be appropriate to use any of these technologies without exercises to prove they work and deliver expected outcomes. The most important conclusion is that MOJ’s work on technology innovation trialling can hopefully work with multiple industry partners and suppliers to make plans to trial the technologies discussed in this paper as a proof of value to determine and quantify the degree to which these ideas could impact on desired strategic outcomes such as reducing prison populations and improving the future lives of those who leave prison.